Mindla Diament was a beautiful woman. We know that from the portrait her older sister Julia Pirotte took of her in Marseille in 1942. In Julia's picture Mindla's face emerges from darkness, classically Semitic, with large eyes, a full mouth, slender neck, and imposing spiritual depth. The two women, born in the first decade of the 20th century in a small town in Poland, had both served prison sentences in their homeland for their communist activities, and had washed up in Paris at the start of WWII. They fled southward to escape the Nazis, and both became active members of the French Resistance. In 1944, Mindla was captured by the Gestapo with documents sewn into the lining of her coat. As she and her friend Marie Dirivaux were being led to the guillotine they called to the prisoners in the death cells, "Courage! Courage!"

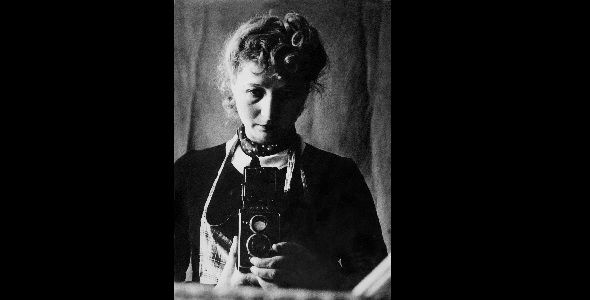

Julia Pirotte was a brilliant photojournalist whose work is little known; the circumstances of her career were such that not much of her work was preserved. A photographic archive in Belgium has the bulk of what remains, and the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw has 400 prints donated to them by the photographer. This spring the Institute mounted Julia Pirotte: Faces and Hands, an exhibition drawn from its holdings, and published a handsome catalogue with the same name. The portrait of Mindla Diament is on the cover.

Julia Diament married Jean Pirotte, a Belgian labor activist, in the 1930s, and studied journalism and photography in Brussels. Her husband was mobilized in 1940 and disappeared: she never saw him again. Julia Pirotte left Belgium for Paris with just her enlarger and the Leica given to her by her friend Suzanne Spaak. The Leica she used throughout most of her career; Spaak was subsequently captured and executed by the Germans. In Marseilles, Pirotte worked for a while as a beach photographer, an experience that helped her develop her skills as a portraitist, especially her feeling for gesture, and in 1942 she became a photojournalist for Dimanche Illustré, a weekly. In the same kitchen where she printed her pictures, Resistance partisans forged IDs, work papers, and other false documents.

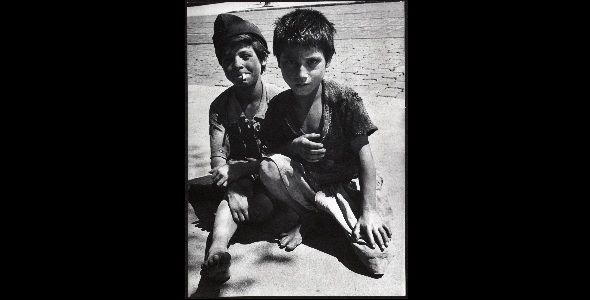

Pirotte's job entitled her to a press ID card that helped her move about, an advantage for both her photography and her Resistance activities. She photographed the citizens of Marseille, the young and the old, in their conspicuous wretchedness. The young seem preternaturally grown: in one picture two street urchins look at her; the boy with a cigarette in his mouth smirks, the other frowns. There is enormous empathy in these pictures, but no sentimentality. She photographed the Bompard transit camp where Jewish women and children were kept before being shipped from Marseilles to Auschwitz.

Among her assignments for Dimanche Illustré, she was responsible for taking pictures of artists visiting Marseilles, which is how she came to take one of the iconic portraits of Édith Piaf. The singer wanted to assume a Hollywood pose, but Pirotte convinced her to be natural. The portrait captures Piaf's haunting fragility, and was one of her favorite pictures of herself. Like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Pirotte could take revealing portraits of people regardless of their status.

At 3:00 p.m. on August 21, 1944, the Marseille Uprising began, and Pirotte participated as a partisan and as a photographer. Her pictures of armed civilians pursuing the German and Vichy soldiers—men in newsboy caps with machine guns, a woman in a helmet wearing an improvised insignia attached to her blouse with a safety pin—are an indispensable record of the city's liberation.

After the war Pirotte returned to Poland. Her younger brother, Marek, a poet, had died in the Soviet gulag in 1943, and both parents were killed in extermination camps. Still an idealistic Communist, she took photographs for propaganda purposes, and in July 1946 was assigned to cover the Kielce pogrom. In that city, the few Jews who survived the war were attacked, beaten and killed by Poles. Pirotte was the only photojournalist in Kielce, and when she returned to Warsaw her three rolls of film "disappeared," she believed on orders from the Communist authorities. The images on display in the exhibition—rows of coffins, bandaged victims in the hospital—are from 16 rough prints she managed to preserve.

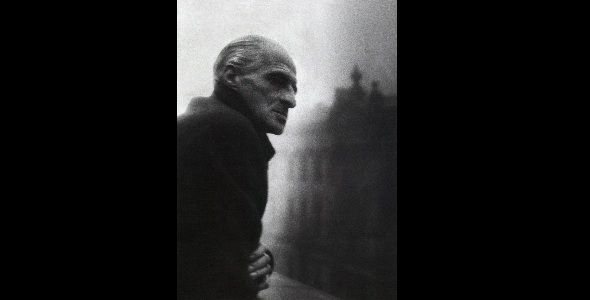

Her portraits of participants in the World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace, held in Wrocław (Breslau) in 1948, are fascinating: the poet Paul Éluard, the scientist Irène Joliot-Curie, and many others, but especially Pablo Picasso. He looks forward with an expression of restrained ferocity, his left hand clutching the arm of this chair; delegates were denouncing his decadent, bourgeois art. Her diminished enthusiasm for Communism waned further when, in 1958, she married Jefim Sokolski, a Polish economist who had spent 21 years in Soviet prison camps.

Pirotte’s portraits of anonymous children and elderly women are among the glories of the Ringelblum exhibition. In 1946, in Poland, she photographed a young boy with a mop of blond hair and terribly dirty cheeks and hands. He wears some sort of traditional pillbox cap and the tattered remains of a white blouse, and looks up at her with great uncertainty. In 1957 she visited Israel, and in Jerusalem photographed an old woman lighting her Sabbath candles. The woman is backlit so the white cloth covering her hair glows and, although her face is in darkness, the back of her hands, which are raised to shield her eyes, are visible; the bones and rough texture tell us all we need to know.

A petite woman, Julia Pirotte dressed and groomed herself simply, but elegantly. Her demeanor was reserved. She was innately modest, but at the urging of a Belgian friend, submitted photographs in 1980 to Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie in Arles, France. She won first prize in this prestigious competition, and the recognition led to articles and several exhibitions, including one in 1984 at the International Center of Photography in New York. In 1996 she received the French Order of Arts and Letters.

Julia Pirotte died in 2000. Teresa Śmiechowska, the curator of Julia Pirotte: Faces and Hands, said to me that the photographer's biography was the history of the 20th century. Szymon Bojko, an art critic who worked with her as a photographer in the 1940s, ends his catalogue essay, "Ach, miała oko! Kochała życie"—"Oh she had an eye! And she loved life."

All photographs courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw; reprinted with permission.

William Meyers writes on photography for the Wall Street Journal. Periferii: New York dincolo de Manhattan, an exhibition of his own photographs, is on display at the Centrul Cultural Palatele Brâncovenesti, Mogosoaia, Romania, through June 20.